An Open Invitation to Care

June 29, 2020 Linfah McQueen

School of Pharmacy student offers a reflection on systemic racial injustice in the United States and the need for health profession students to get involved in turning the tide.

This is the most difficult piece of writing I have ever tried to do. Others who know me know that words seem to run — sometimes too well or unguarded — from my mouth and in my writing. Putting pen to paper today, however, has posed a challenge.

To understand my challenge, let’s revisit a discussion from Professional Foundations of Pharmacy about “imposter syndrome” with Brent Reed, PharmD, associate professor, Department of Pharmacy Practice and Science, at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy (UMSOP). The goal of that discussion was to explain why people who have achieved greatness and have the potential to accomplish amazing things often fail to believe that they are knowledgeable or qualified enough to have earned their place. As a result, these people feel like they do not deserve the opportunities available to them. For the first time in a long time, I am experiencing imposter syndrome.

Let me tell you why.

I have long wanted to talk to my classmates and peers about covert racism and how our current police system, which originated from organized slave patrols, has evolved into what it is now: a rotten egg of police brutality tied in a pretty blue bow. However, I find myself too unknowledgeable, too unqualified, and too new to this conversation to attempt to give anyone a history lesson about the systematic oppression of Black people in America.

Now, don’t get me wrong. As a Trinidadian, I am the descendant of slaves. But, if you are familiar with slavery in the Caribbean, you will agree that it was a completely different experience that calls for a completely different conversation. Instead, if you’re up for it, let’s just have an honest dialogue.

Before we get started, we must accept that those of us who are new to the conversation of police brutality are new because we have had the privilege of this conversation not being paramount to our survival — our chance of living to see another day has not depended on us knowing to never reach in the glove compartment if the cops pull us over; never go for a walk at night while wearing a hoodie; or never let your guard down, even when sleeping comfortably in your bed, because it seems you can be killed there, too. We must recognize that we live a totally different reality from others who have grown up hearing these conversations every day, even some of our friends in pharmacy school.

Now that those of us who are new to these conversations have acknowledged our privilege, we can begin the discussion that I wanted to have with all of you, which is: What type of pharmacist do you want to be?

I ask this question because we must understand our responsibility as future pharmacists within the context of the power and effect that we will have on the lives of others in our careers. In his discussion, Dr. Reed did a great job explaining to us the havoc we can we wreak in patients’ lives by choosing to remain ignorant to the uniquely difficult experience of life, as a member of a disenfranchised population. Pharmacy schools as well as other health profession schools are churning out health care providers who have the knowledge needed to do the tasks they must. Yet, where they have failed both students and the patients we will treat is not ensuring that every person who earns the prestige that comes with being a UMSOP-trained pharmacist becomes a better person — a person capable of empathy and care for each unique individual we will treat.

I talk a lot about Dr. Reed’s class, because it is the only required course in our curriculum that provokes any thought that extends beyond operational competence in our field. All other cultural competence classes are offered as electives, because we as a profession place more value on understanding the medical conditions we treat, instead of better understanding the people we treat. Courses like the one taught by Dr. Reed are rare. They force us to reflect and think about complex topics that we might not otherwise encounter but are often the first targeted when credits or hours must be reduced.

If we agree on anything today, it is probably this: Our experience at UMSOP is far from ideal. However, regardless of our hardships, we all recognize that our administration and faculty care for their students and the types of pharmacists they produce. We know that we always have their ear. Skeptical about that? Think back to a day you sat in your classroom for a lecture. What do you remember? That one girl who would fall asleep, like clockwork, 10 minutes into every lecture? The guy in the back who asked too many questions? The girl who raised her hand to answer every question the professor asked, but always gave the wrong answer? The way the class lit up when your favorite professor entered the room? Perhaps. However, I would argue that the one thing that was impossible to miss was the diversity in culture, color, religion, sex and gender identities, and age that existed amongst the members of your class.

This is not a coincidence.

The fact that your learning space is a blended melting pot of people from different cultures, ethnicities, religions, and demographics is by design. From Day 1, our School of Pharmacy made it clear that its intention is to produce a diverse population of highly trained pharmacists. While there are many improvements that could still be made to make this goal more attainable, we can agree that the intention is apparent in the people we sit next to in class.

Why is this profound? As student pharmacists, UMSOP’s quest to educate and train a diverse population of future pharmacists provides us with a niche opportunity — the opportunity to live with, work with, and listen to a compendium of people who will enrich our life experiences with their differing perspectives and realities, if we make ourselves open to it. Some of you might say, “Linfah, you are preaching to the choir. I’m friends with people from a lot of different cultures and nationalities.” Let’s explore that. If you have an Indian friend, have you been invited to their apartment for Malai Kofta? If you have a Trini friend, can you locate Trinidad on a map? If you value the rights of your lesbian friend, why do you denounce these same rights for trans individuals? If you have a Black friend, how do you not see the systematic oppression that they battle every day for the same opportunities that your privilege affords you?

That said, only those without sin can cast stones, and I am in no way fit to throw any stones your way. We can all do more and we can all do better.

We are all works in progress, and while I understand that we are all fighting different battles, we cannot continue to ignore our classmates’ calls for love and action at a time when they are literally fighting for their right to exist. My goal is not to call you out, but if this conversation makes you uncomfortable, reflect on why. I am writing to do one thing: provoke thought. If you are still working out how you feel about our current environment, that’s fine. If you are changing your mind about how you feel, that is fine, too. However, you must understand that if you want to be a good pharmacist, you must be a good person first. You need to recognize that if you do not care for anyone other than those who look like you, YOU ARE NOT A GOOD PERSON. If you are working on it, that’s fine, but understand that you must continue to do the work.

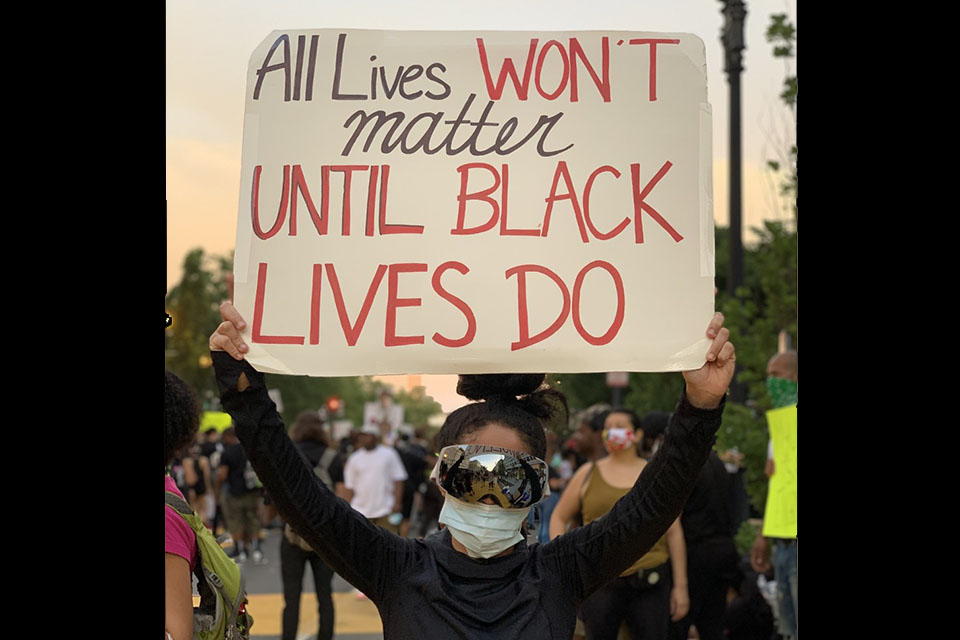

As a person who checks all of the boxes of the disenfranchised, please listen to me when I say how important it is to have a vocal ally who shouts into every uninviting space that my existence is necessary, that my life matters. While I would be crazy to expect this conversation to magically make you more socially aware, I am inviting you to begin opening your eyes to the challenges faced by others around you. I am inviting you to explore why you feel uncomfortable when it seems like all of your classmates’ social media posts are about police brutality and racism. I am inviting you to reflect on why you validate your lack of interest in rallying in solidarity with Black Americans — many of whom you sit next to in class — by saying your life as an immigrant, LGBTQ individual, or other disenfranchised group is harder or even comparable to the plight of Black Americans. I am inviting you to reflect on what your silence, when your dad says something racist at the dinner table or your cousin posts a racist joke in your family group chat, actually means. I am inviting you to care about the patients you will serve as a health care professional, regardless of their social history. I am inviting you to care about your classmates, who you go into the trenches with every single day on the journey to becoming a pharmacist. This is an open invitation: to care.

Linfah McQueen is a second-year student at UMSOP.