My Social Work Ancestors Are Vietnamese, Buddhist, and Anti-War Peace Activists

May 01, 2023 Vi Bui

This Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, uplift social workers of Asian ancestry.

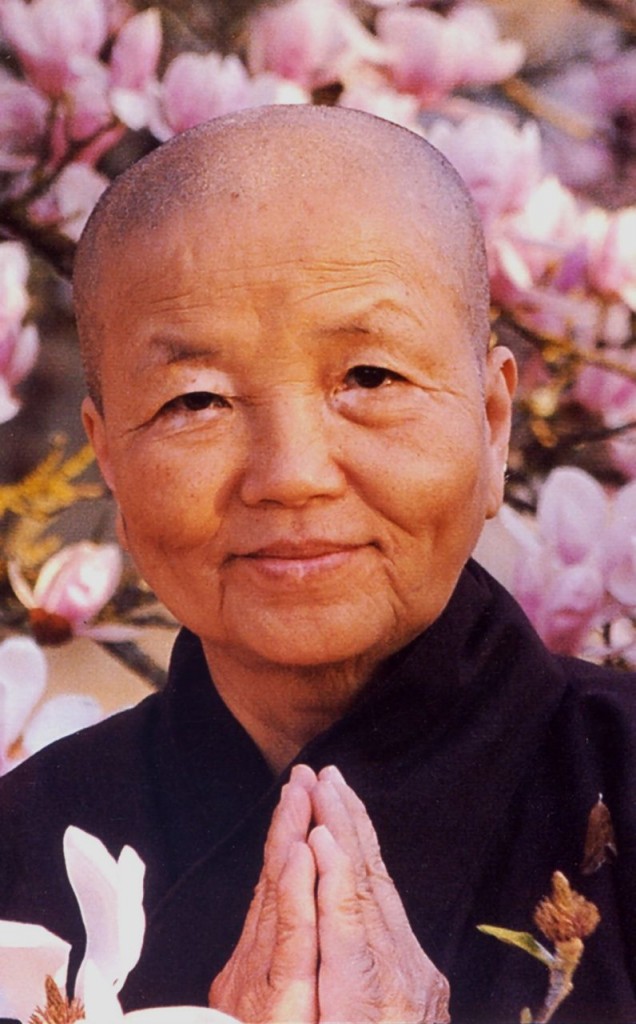

While the narrative about social work in the United States is that it has been primarily carried out by upper- and middle-class white Christian women, there has been increasing recognition of the contributions of Black and Indigenous social workers who have played significant roles in the field. This Asian American Pacific Islander Heritage Month, I wanted to uplift a social worker with my ethnic heritage, and there is no one I would consider more of a personal social work ancestor than Vietnamese Buddhist nun, anti-war peace activist, and social worker Sister Chân Không.

Chân Không and the School of Youth and Social Services

Chân Không was born Cao Ngọc Phương (family name: Cao, given names: Ngọc Phương) in 1938 to a middle-class family in the Mekong River Delta of Vietnam. Since childhood, Chân Không engaged in self-directed charity work, providing financial aid to other children who experienced poverty. During her time at the University of Saigon, Chân Không would visit the nearby slums and help the families by organizing projects and resources to improve health care, education, and economic development. Her passion was to pursue both social work and Buddhism, but she did not find a spiritual teacher who supported her vision until she met Thích Nhất Hạnh in 1959. Together in 1965, Chân Không and Thích Nhất Hạnh established the School of Youth for Social Services (SYSS) as the first social work school in Vietnam with the idea to create partnership and understanding between the poor villagers and social work students, and to guide the development of the students through personal and social transformation. Chân Không led its operations and alongside 10,000 social workers and volunteers partnered with villages to establish schools and medical centers when the government failed to address their advocacy efforts.

However, being Buddhist in 1960s South Vietnam became increasingly dangerous as President Ngô Đình Diệm sought to make South Vietnam into a Catholic country and the Buddhist social work movement faced state violence. Their work with the poor and victims of violence on both sides of the war and commitment to nonviolence made them political targets, as this was seen as a Communist activity, despite their refusal to align with any political movement. Chân Không witnessed many of her peers be persecuted, kidnapped, and murdered for their work. To get them through such traumatic circumstances, Chân Không and other members of the Buddhist social work movement cite their spiritual practice and mindfulness to keeping their hope alive. Eventually the School of Youth for Social Services was dissolved, but the spirit and teachings live on in the continued spread of what came to be known today as Engaged Buddhism.

The Legacy of Engaged Buddhism

After Thích Nhất Hạnh was exiled from South Vietnam for refusing to take a side during the U.S. war in Vietnam, he and Chân Không established Plum Village in 1983 in Southern France, which acts as the central hub and community of Engaged Buddhism, now practiced all over the world. Engaged Buddhism is a practice of Buddhism that confronts social injustice and participates in political activism. Elements of Engaged Buddhist practice also stem from the Dalit Buddhist movement founded by B.R. Ambedkar rejecting the caste oppression of Hinduism. Chân Không has said, “People think that engaged Buddhism is only social work, only stopping the war. But, in fact, at the same time you stop the war outside, you have to stop the war inside yourself.” Through Thích Nhất Hạnh and Chân Không’s writing, lectures, and Dharma talks, Engaged Buddhism and the related teachings of mindfulness have spread all over the Western world and are now commonly used by many mental health clinicians and healing practitioners. Although Thích Nhất Hạnh died in January 2022, Sister Chân Không at age 85 continues to be a spiritual teacher and leader of social justice.

Learning Lessons from Chân Không’s Life and Work

Chân Không’s work in the villages caught in the crossfires of war, demonstrates that micro and direct practice social work is never disconnected from the macro practice of upending the systems and forces that create suffering. Further, the field of social work needs to take an international perspective and recognize the ways in which the United States and other Western powers contribute to violence, oppression, and crises across the globe. The School of Youth and Social Services’ foundation in Buddhist principles also underscores the importance of having a strong set of values to act as a guide and compass in social work practice. It is also clear that faith, or a sense of hope or optimism, regardless of religious belief, is an important element of social change work to get through challenging circumstances. Faith is what guided Chân Không, just as it did the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and the Catholic liberation theology movement in Latin America.

The field of social work needs to expand its definition of what social work is outside of whiteness. Professionalized social work erases the contributions of those who have provided mutual and community care outside of traditional institutions. At the same time, non-Western spiritual and healing practices, such as meditation and mindfulness continue to be co-opted and appropriated by the professional mental health field. Decontextualizing the mindfulness practices spread by the teachings of the leaders of Engaged Buddhism from its critiques of oppression and violence, and, further, using them as tools to expropriate greater productivity and profit is a misrepresentation and misuse of these philosophies. Social work practitioners who use these now “evidence-based practices” need to not only recognize their origins, but also act in alignment with the teachings and philosophies from which they originate.

As we continue to recognize Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, I hope Chân Không can serve as a new inspiration for what a radical social work practice can look like. Asians and Asian Americans have a rich history of involvement in social change, civil and human rights, and I am proud to be a part of its lineage.

To learn more about Sister Chân Không and the School for Youth and Social Services, please check out the following sources:

- Autobiography: "Learning True Love: How I Leaned and Practiced Social Change in Vietnam" (1993) by Sister Chân Không (The newer edition of this text was published in 2007 with the title "Learning True Love: Practicing Buddhism in a Time of War")

- Sister Chân Không’s biography by Plum Village

- Article: "The Life and Teachings of Sister Chân Không" (2017) by Andrea Miller for Lion’s Roar

- Blog and interview with graduate of SYSS’ inaugural class: "Mindfulness in times of war. The School of Youth for Social Service" (2016)

Vi Bui is an intern with the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at the University of Maryland School of Social Work.

Disclaimer: Elm Voices & Opinions articles reflect the thoughts or opinions of their individual authors, and may not represent the thoughts or values of UMB as an institution.